Domain-driven design essentials - Key Concepts

Chapter 1

Introduction

In the last 10-20 years, a huge hype has accumulated around microservices and domain-driven design (DDD), and rightfully so. I am writing this body of articles as a way for me to lay down my exploration knowledge I have accrued on the topics and share it with other curious people. I will be focusing specifically on DDD, but we will also briefly talk about Mircroservices architectural style and why DDD and microservices compliment each other so well. To illustrate core topics two projects are provided, source code for which is located here, a project about building a blog (simplistic project) and a project about building a car rental business (advance project).

Resources

A huge inspiration for me has been the work of Eric Evans, the so called “Blue book”, Jimmy Boggard, Julie Lerman, and to a degree Martin Fowler. My advice for you is to check them out post reading this body of work, as their creation is not necessarily targeted at introductory level. The latter statement is especially valid for the Blue Book, even though I find the non technical path as a bit easier.

What are we solving with DDD and why DDD?

Software in the last 20 years has evolved a lot. Software is everywhere. Every business has software, every business is trying to automate some processes so it can save on costs. We are literally in a “software revolution” lead by the business.

This war on evolving your business, and it’s software with it, creates a new level, a level which makes the softwares more heavy, more bloated, a level that brings more business complexity in the software domain. This makes implementing software solutions harder than it was 10 years ago. I was not a software engineer 10 years ago, so this is not a first hand account of the events, but by reading different books and articles you can see the picture.

Let’s start talking tech, if we take one .NET Core MVC, or Unity project, WPF project whatever… each one of these technilogies gives us a “front-end” pattern, a well developed and a well structured one, they are great (but!). MVC for example has Models, Views, Controllers, everything is separated and it has it’s own responsibilities - perfect. However if we have complex business logic, and as I mention the business has started bringing more complexity, even a simple application can become a plate of “spahetti” in no time. So if we are just using the classical pattern via MVC, we will soon have Controllers that are too long and contain a lot of business logic. This in itself does not sound too bad, if we imagine this application is developed by 5 developers and 2 QAs for a company that has 50 employees, however if we take this example and try to apply it to a corporate enviourment, this classical pattern is just not enough. The standard approach to solve this problem is to move the logic from the Controllers into the Service layer, via creating multiple services. And this is not wrong, it just has side effects. For example as the Service layer increases different services start talking between each other, we have servies that have pure business logic, and some that contain infrastructure logic, but often we have a mix of logic inside a single service.

What DDD is trying to do is separete the responsibilities, creating new objects, persisting in the DB and just pure business logic. The latter are things that do not dependend on anything else, those are things that I can write in plain C# code, without even installing one nuget packet. In other words DDD is trying to not only separe our infrastructe logic, persistent logic (as we are already used to) and so forth, but take the business logic and split it and cathegorize it into different elements, this makes the code cleaner and easier to work with.

Server side architectures

DDD is not only usable on the server, however our focus will lay in this area Architecture on High-Level is when we have an application an we are talking how do the different elements of it communicate, persist data etc. A classical example of this is when we talk about Ecommerce site. You have a Catalog, Shopping Cart, Product and Order elements, high level architecture deals with things like 1) messages between elements for example via RabbitMQ, 2) caching, 3) Data persistent per elements, 4) use of External Services for example PDFPrinter, 5) Cloud Infrastructure for example via Docker/K8s and so forth.

Architecture on Low-Level is when we take one of those elements, for example the Catalog, and how to structure the code in it - how to separate the controllers, the business logic, the data … etc. So a question arises what are the characteristics we looking for when we are designing our application low-level architecture.

Elements of an architecture

Separation of Concerns means every internal element of an application should be separated. We could for example have one file Models.cs containing all of our Models, but that is not ideal as that file will grew exponentially and maintaining it will be nightmarish. In other words each object should have clear responsibilities. Encapsulation on the other hand is a simple mechanism that we use to protect ourselves from creating/modifying objects in invalid state. Doing this leads to less bugs in our code. Dependency Inversion is decoupling of dependencies, so if I have a service that depends on the database I should use abstractions - interfaces instead of concrete implementation. This makes all dependencies interchangeable. ; Explicit Components is the idea that we know what a class does, what is the role of the class in the whole system, just by opening it - it’s very clearly designed/named; Single Responsibility of the different software elements; Don’t Repeat Yourself simply put don’t copy/paste the same code in different elements; Persistence & Infrastructure Ignorance so my code works without caring what DB we use, or do we deploy this on a Virtual Machine or a k8s cluster; Similarly to the previous principle Presentation Ignorance dictates that the UI layer of the element should be easily interchangeable;

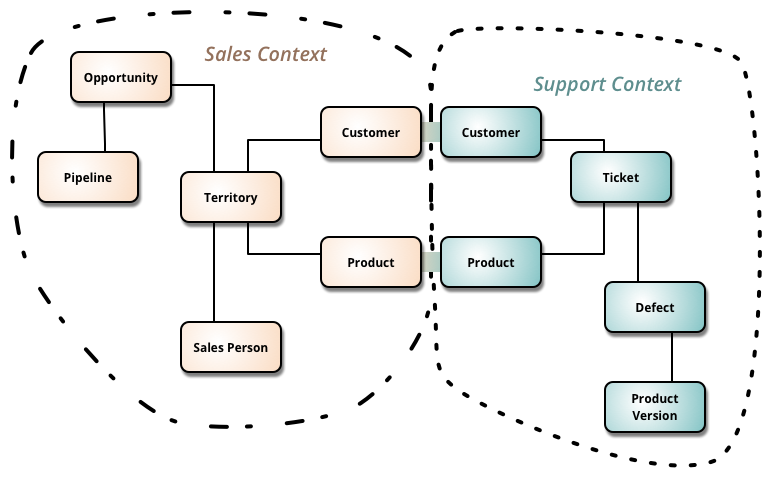

Fig. 01 Example of contexts use from Martin Fowler

Bounded Contexts is a central idea of DDD, its the the idea of how to deal with large models and teams. We do that by splitting them into different contexts and defining explicitly their interrelationships. In the example above, we can see that the interrelationships are the customer and product however each of the different teams (sales and support) has additional models about things they need information about. Sales is interested in who sold the product and via what sales pipeline, while Support is more interested in did that product have defects, how many issue tickets there are and so forth. The key aspect is each of this contexts can work by itself - If we do not offer support, for example, then Sales should be able to function without it. This is a brief overview and we will examine it indebt later on; Testability

| Principles | Classical Approach | DDD Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Separation of Concerns | not fully (Service layer when it grows) | fully |

| Encapsulation | not fully (especially Entities from the DB) | fully |

| Dependency Inversion | fully | fully |

| Explicit Components | fully | fully |

| Single Responsibility | fully | fully |

| Don’t Repeat Yourself | fully | fully |

| Persistence & Infrastructure Ignorance | not supported | fully |

| Presentation Ignorance | not supported | fully |

| Bounded Contexts | not supported | fully |

| Testability | fully | fully |

The classical approach

Fig. 02 Example of generic 3 tier server architecture

The classical approach (or also known as 3-Tier server architecture) is the idea that the database is the center of the application. So we setup the database and we start moving upwards, in other words we can not do anything until our database is designed.

The biggest pros of why this is taught and used so widely, is its simplicity, the fact that most people understand it well and it covers a huge chunk of our architectural needs. Now talking about pros without cons is no balanced, so we need to mention that this is not a flexible architecture, it is designed for single presentation applications (before smartphones), it does not scale well - extracting microservices is a challenging task, and all dependencies are towards the database.

The Domain-Driven Design approach

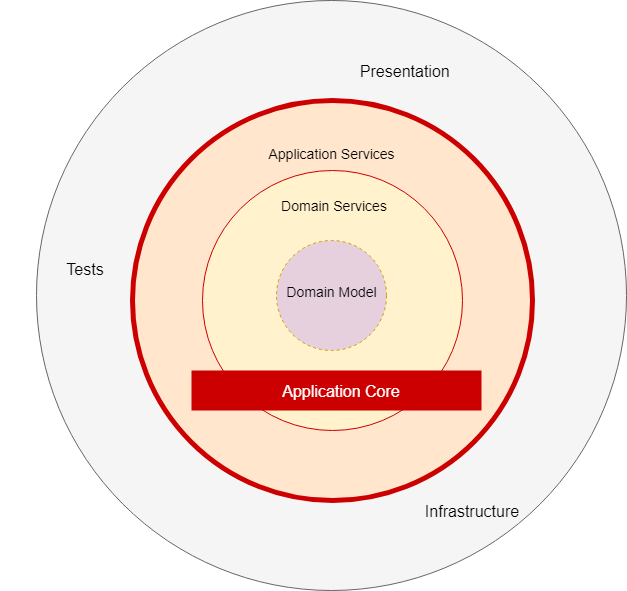

Fig. 03 Example of DDD onion architecture

The domain-driven design approach is the idea that the business domain is the center of the application. So here a key idea is solving problems, understanding client needs and then writing the code. In order to do this we communicate with domain experts to design our solution. We do not care about the database, we do not care about the presentation, all this is just a detail. This approach has success with complex projects.

The pros of this architecture are it’s flexibility, the idea that the customer has better vision/perspective of the problem, the systematic path through a very complex problem, well organized and easily tested code, all the business logic lives in one place, and the option to leverage multiple patterns internally. Of course everything that sounds so cool comes with its drawbacks, as if such do not exist everyone would use this approach. We need more time - to talk and model the problem with the domain experts, to isolate domain logic from other parts of the application etc. The learning curve is huge - New principles, patterns, processes. The need for complexity - it makes no sense to use this for just CRUD or data-driven applications, it only makes sense to use it when there is complexity in the problem and not just technical complexity without business domain complexity.

To sum it up:

DDD is superior as it’s scalable in terms of development (when our dev team increases), code has even better separation than the classical approach, it covers all of our architecture needs and it offers improved patterns and flexibility. On the other side it is only usable when the business logic is complex and it is more time-consuming as it needs more classes and relationships between them.

DDD is not treating writing code as only part of the equation needed to solve the problem, the other part is speaking with domain experts, so that we can use the same language in our code as in real life. Our domain model should literally scream (the term is screaming architecture) the business requirements and our classes and methods should describe the actual process.

The Domain Model

The Domain Model is your organized and structured knowledge of the problem. The Domain Model should represent the vocabulary and key concepts of the problem domain and it should identify the relationships among all of the entities within the scope of the domain.

The Domain Model itself could be a diagram, code examples or even written documentation of the problem. The important thing is, the Domain Model should also define the vocabulary around the project and should act as a communication tool for everyone involved. The Ubiquitous Language is an extremely important concept in Domain Driven Design and so it should be directly derived from the Domain Model.

We will use the following generic document structure as our Domain Model

- Problem Domain

- The problem your software is trying to solve

- Core Domain

- The part of the business that must be perfect, and cannot be outsourced

- Sub-Domains

- Separate business problems which can work isolated in theory

- Bounded Context

- A specific responsibility, with specific boundaries that separate it from other parts of the solution

- Shared Kernel

- Part of the model, which is shared by two or more teams

Let’s take the above mentioned generic Domain Model and apply it to a Veterinary Clinic.

- Problem Domain

- We need a system for a veterinary clinic

- Core Domain

- Obviously, the business cannot exist without examinations and surgeries

- Sub-Domains

- Appointments, billing, visit records, medical records, etc.

- Bounded Context

- Appointments will need a Patient model, medical records too, but they are different

- Shared Kernel

- Clients are part of all domains

So is that all? Are we done? Well not really, this is an iterative process, refining our domain model and it’s done with domain experts. But what if we have created a startup and there are no domain experts on hand? Then you are the domain expert.

Continuing with our example, we sit down with the chief nurse and start talking as we need to talk with the client to understand the business needs.

- Clients (people) schedule appointments for patients (pets)

- Appointments may be either office visits or surgeries

- Office visits may be an exam requiring a doctor, or a tech visit

- Office visits depend on exam room availability

- Surgeries depend on operational and recovery space availability, and can involve different kinds of procedures

- Different appointment types and procedures require different staff

Once at this point we have a bit better representation of what the normal business workflow is. Then we can start defining our primary models a bit better also.

- Main models:

- Client can schedule a Patient (pet)

- Schedule is for Appointment or Surgery

- Appointment requires a Doctor and Exam Room

- Surgery requires a Doctor, an Operational Room and a Recovery Room

The above models define the appointments bounded context

- The medical records bounded context will also require a Patient model

- But with different properties and operations

Now that we have this common language, we need to transfer the domain models in the code. We already know that domain models are the heart of the software, but it is important to stress that they are not bound by technology. They are pure classes, that follow the SOLID principles, containing the business logic and business rules. So when designing don’t think about where are you going to persist them and how, don’t think about databases, ORMs etc. our models should be persistence ignorant!

Identity of the Domain objects

Domain objects are used to express the model, before we transition to them let’s answer a “simple” question, how do we know if two objects are equal? To answer that let’s revisit the types of equality you have in programming, these are identifier equality, value equality (also known as structural), and reference equality.

Identifier equality - Objects are equal, if their ID is equal

Structural equality - Objects are equal, if all their properties are equal

Reference equality - Objects are equal, if they use the same memory address

Reference and structural equalities are pretty straight forward, however when talking about identifier equalities we have a couple of strategies we could use to generate those unique identifiers.

The standard “database identity” is usually integers which are autoincremented. This works great, but you cannot have the value before saving the entity. Taking this in con in mind we have GUIDs we know those beforehand and we use them when we need the value before saving the entity, however this created a need for a separated indexed column, which makes them slowed than the Identities. And lastly we have [Hi/Lo (algorithm)](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hi/Lo_algorithm#:~:text=Hi%2FLo%20is%20used%20in,universally%20unique%20identifiers%20(UUID).. the idea of this value generation strategy is that you know the values before saving the entities by using a sequences of available identities provided from the database. This works like identities, but since we ask for sequences the database is called less frequently.

Knowing what is the domain model, what are the different equalities, what is identifier, and what are the different strategies for generating an identifier, our next logical step is towards the different type of objects in our domain.

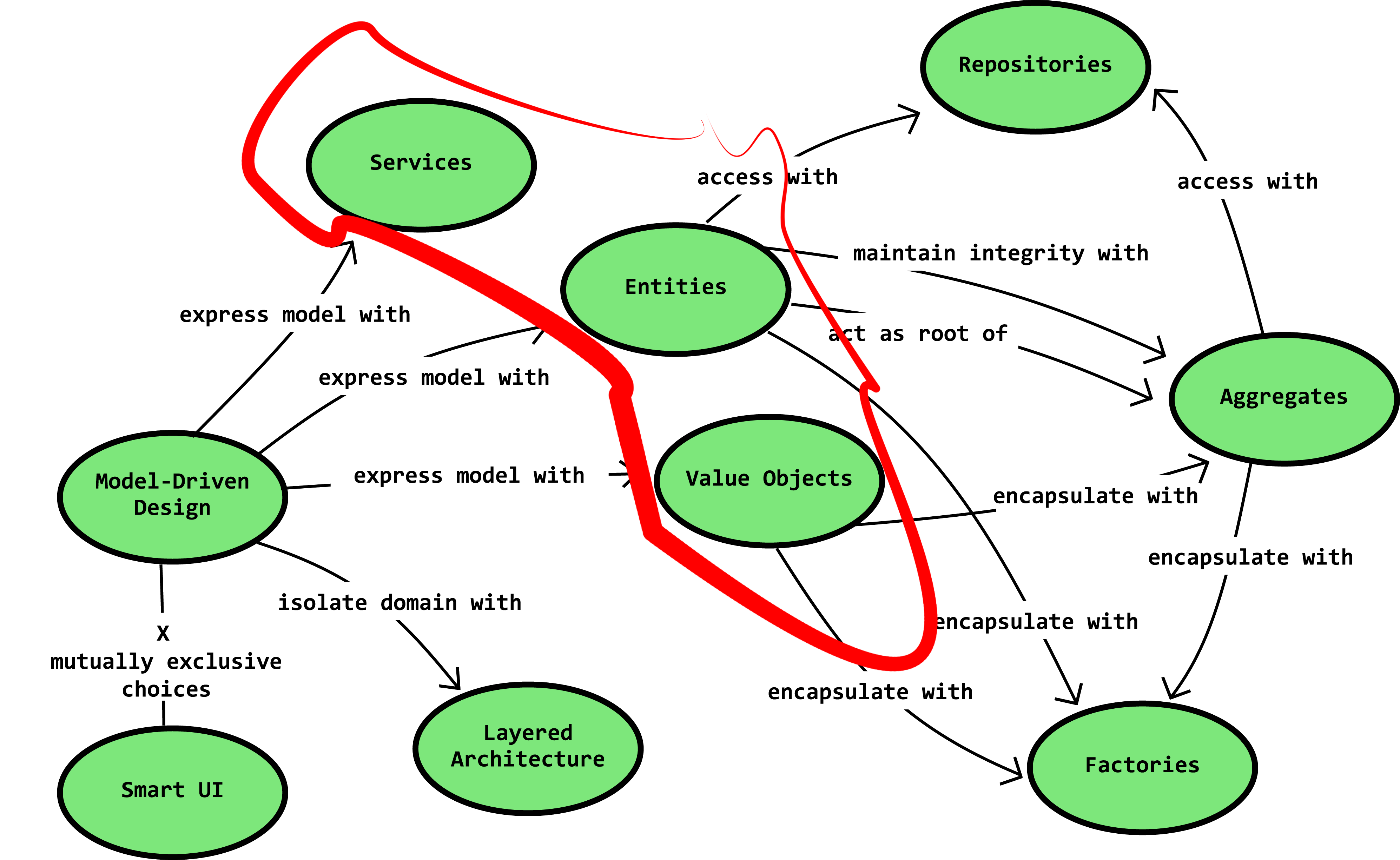

Fig. 04 DDD diagram for Domain objects

Entities

Entities are pretty much the bread and butter of domain modeling. They are objects in our Domain Model with an identity and a lifecycle. The primary traits of entities is that they are objects that have an id, which are considered equal if those ids are equal. Entities have mutable state, of course if our domain model (business logic) permits that, and that mutability is done trough methods and behavior. Keeping entities encapsulated with private setters and using public constructors only if those constructors are able to create object in valid state. If any collections exists in our entity those should be read-only.

*!NB DDD Entity != EF Entity*

C:\Car Dealers\Domain\Models\Dealers\Dealer.cs

1 namespace CarRentalSystem.Domain.Models.Dealers

2 {

3 using System.Collections.Generic;

4 using System.Linq;

5 using CarAds;

6 using Common;

7 using Exceptions;

8

9 using static ModelConstants.Common;

10

11 public class Dealer : Entity<int>, IAggregateRoot

12 {

13 private readonly HashSet<CarAd> carAds;

14

15 internal Dealer(string name, string phoneNumber)

16 {

17 this.Validate(name);

18

19 this.Name = name;

20 this.PhoneNumber = phoneNumber;

21

22 this.carAds = new HashSet<CarAd>();

23 }

24

25 private Dealer(string name)

26 {

27 this.Name = name;

28 this.PhoneNumber = default!;

29

30 this.carAds = new HashSet<CarAd>();

31 }

32

33 public string Name { get; private set; }

34

35 public PhoneNumber PhoneNumber { get; private set; }

36

37 public Dealer UpdateName(string name)

38 {

39 this.Validate(name);

40 this.Name = name;

41

42 return this;

43 }

44

45 public Dealer UpdatePhoneNumber(string phoneNumber)

46 {

47 this.PhoneNumber = phoneNumber;

48

49 return this;

50 }

51

52 public IReadOnlyCollection<CarAd> CarAds => this.carAds.ToList().AsReadOnly();

53

54 public void AddCarAd(CarAd carAd) => this.carAds.Add(carAd);

55

56 private void Validate(string name)

57 => Guard.ForStringLength<InvalidDealerException>(

58 name,

59 MinNameLength,

60 MaxNameLength,

61 nameof(this.Name));

62 }

63 }

is a source code example of all the statements above.

Entities relationships

When modeling in the classical approach we usually model things in a two-way relationships quite often. We say Article has Comments, and Comments has Article. We try to avoid this in DDD - do not use two-way relationships except in cases where it makes business sense. sense Because using a bidirectional relationship means that the objects can live only together. If possible use one-way relationships and avoid using foreign keys. This simplifies the design, and makes sure associations make business sense.

We will talk a bit more when we start discussion the Infrastructure, but let’s just quickly mention (since panic ensures when you typically say do not put FK in a model), that we can have reusability and EF can use the domain models for the creation of the database, but we can also have a totally new classes which inherit the domain models. The important take here is, on the level of Domain we do not care about persistence, foreign keys, primary keys, at this layer we simply don’t care about that. When we reach the persistent layer we will work with foreign keys and that will be outside the domain layer.

Value objects

A Value Object is an immutable type that is distinguishable only by the state of its properties. That is, unlike an Entity, which has a unique identifier and remains distinct even if its properties are otherwise identical, two Value Objects with the exact same properties can be considered equal. Most importantly value objects are immutable and cannot be changed once they are created.

Since they are immutable modifying one is conceptually the same as discarding the old one and creating a new one. Frequently, the Value Object can define helper methods (or extensions methods) that assist with such operations. The built-in string object in the .NET framework is a good example of an immutable type. Converting a string in some manner, such as making it uppercase via ToUpper(), doesn’t actually change the original string but rather creates a new string. Likewise, concatenating two strings doesn’t modify either original string, but rather creates a third one.

A classical example to illustrate Value objects is Money

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

public class Money

{

public SomeValue(int amount, string currencyCode)

{

this.Amount = amount;

this.CurrencyCode = currencyCode;

}

public int Amount { get; private set; }

public string CurrencyCode { get; private set; }

}

If we have an Ecommerce shop that has a product catalog, and each product has a price and currency, if we just leave it in the product model then it has to take care of validation of those properties, and any other model dealing would product then it will have to deal the price and currency. So a better solution to that is to group those properties into one object and that Object is the Value Object. Extracting this logic means that it is impossible to have somewhere in my application amount without currency or currency without an amount.

To summarize the idea of Value object is to create objects that group together properties that make sense to exist only together, but do not have an ID. Making this objects immutable avoids the side effects of having an invalid object state.

Enumeration

A huge chunk of this paragraph is based on Enumeration classes by Jimmy Bogard.

Enumeration is just a standard enumeration we all know from C#, however DDD suggest that we create a base class for your enumeration types, that provide common enumeration logic. This provides more flexibility , as we can write methods related to them and use inheritance to pass them down the chain. It is more OOP-oriented than the built-in enum, and it allows you to stop using enumerations for control flow.

This of course is not a requirement of DDD, as you could see from Fig. 04, it’s not a critical topic and does not matter that much, however this is a good practice and that’s why we discuss it.

Anti-patterns when designing Domain Objects

Using plain POCO like we would typically do when creating an EF Entity is a big mistake, because we are missing on validation and encapsulation.

Another thing is if Domain objects have unnatural responsibilities that is not pure business logic, classical example is sending emails, rather infrastructure related.

Another critical thing is that communication with external layers is “forbidden”, as domain objects are the objects of the lowest level they only communicate between each other.

Lastly using generic exceptions is something to be avoided. If I am creating an object and it fails the validation I need to know why it failed it. A generic exception “fail validation” is of no use, which part of the validation did it fail? A general solution is to create a specific Exception class for each domain mode, this let us trace much more easier in which domain is the exception raised.

Domain Services

Domain services contain domain logic, which cannot be put in the domain classes directly, because for example it depends on a few domain models. They do not communicate with the outside world. They should be stateless, and they should have interfaces. Lastly they do not use DTOs rather they should use only the domain models.

A classical example is when we would like to transfer money from one account to another, it just makes no sense that one account object takes another account object and sets properties in it. Another example we could use is when we are processing our shopping cart to create an order, it makes no sense that the shopping cart is able to create orders as this is practically two different bounding contexts.

To summarize we create a domain service when we have business logic which is plain weird to stay inside a domain model. Most importantly there is no Database, Files, Mails, or other infrastructure logic, also no JSON/HTTP or other presentation logic.