Common C# Traps

Traps

Equality in .NET

In the C# language we have 2 types of equality Value equality this is just like in math this is understood to be so if their values is equal. For example 5 is equal to 5 and so forth. In C# we say that two objects have value equality if the data written in them is absolutely the same. E.g. two integers with the same value have value equality.

The second one is Reference equality this is also known as identity. Two object references refer to the same object.

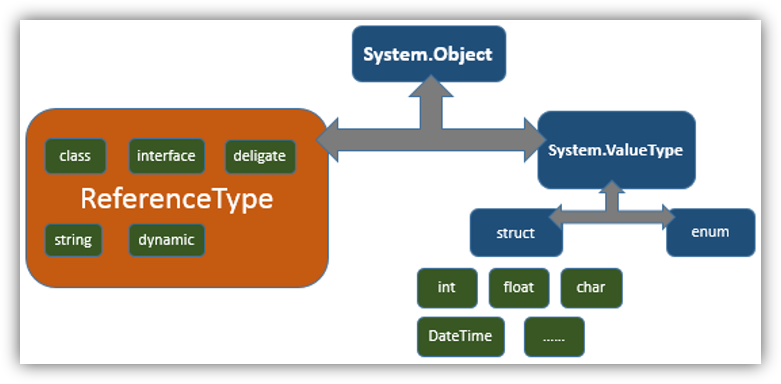

In order to better understand equality, lets familiarize ourselves with the C# object hierarchy. The Object class is the base class for all the classes in .Net Framework. It is present in the System namespace. In C#, the .NET Base Class Library(BCL) has a language-specific alias which is Object class with the fully qualified name as System.Object. Every class in C# is directly or indirectly derived from the Object class. If a Class does not extend any other class then it is the direct child class of Object class and if extends other class then it is an indirectly derived. Therefore the Object class methods are available to all C# classes.

To check for reference equality, use ReferenceEquals (returns Boolean)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

object.ReferenceEquals(firstObject, secondObject)

}

}

This is if we are sure that we want to check reference equality, but in most cases that is not what we need.

To check for value equality, you should generally use Equals method. Equals as it is implemented by Object just performs a reference check (we should override it).

By default, the operator == tests for reference equality, of course an exception is everything belonging to the System.ValueType, string (because it is overriden there) , but if in your class “Student” you use == operator you will compare references.

So a struct is a ValueType, but A struct can have inside reference types, so how does that work? By default when comparing structs with Equals(), if none of the fields of the current instance are reference types=> byte-by-byte comparison, otherwise it uses reflection to compare the corresponding fields (~20 times slower!). We can improve the performance of structs by comparing them with overridden Equals.

String references

String is a reference (class) and immutable type. That means that a string once made can not be changed, extended or switched. One more unique string thing is, how they are placed in memory. Yes they are in the Heap, but for them we make this special “String table”. The official definition is that CLR uses a method of storing only one copy of each distinct string value (string interning). We use this special table in order to save memory, for example if we want one string to be assigned to another string, then instead of making a new object in memory we just use the one we already have in the reference table.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

var string1 = "some value";

var string2 = "some value";

// ReferenceEquals(string1, string2) is true <-Uses the string table

// So even thought it is two objects, it compares the same reference from the table

var stringFromConsole = Console.ReadLine(); // "some value"

// ReferenceEquals(string1, stringFromConsole) is false

// Because this is a string not generated on compile time it is not in string table

// So it makes a new object.

var stringIntern = string.Intern(stringFromConsole);

// ReferenceEquals(string1, stringIntern) is true

// Works because we force the compiler to retrieve the system's reference to the specified String.

}

}

Just a common note, if we have a string to which multiple times we apply the += operator, maybe we should use some sort of a Buffer structure like StringBuilder. As we know when we apply the += operator a new pointer to new string is created, this means that we for the GC to collect and so forth, this is not memory efficient.

Preserving Stack Trace

One important thing when figuring out which part of your code functions suboptimal is Exceptions. Exception have a “path of origin” also known as Stack trace or from which method did this exception originated. We often have cases where we would want to catch an exception in a certain method of the trace and then attach additional information.

If we do it like this, the trace would be preserved:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

try { … } catch () { throw; }

try { … } catch (Exception e) { throw; }

}

}

However if we we would like to change the source and the Stack trace we can do it like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

try { … } catch (Exception e) { throw e; }

}

}

It will appear that the exception has been thrown from the current method from that very line. This is acceptable, however not best, practice. Generally it is recommended to create a new custom exceptions.

Exceptions & Static Constructors

So what happens if we have exceptions in a constructor of a class?

Every class, regardless of static or not, has an empty constructor, one static and one “normal”, that we can not remove. We can of course override it, but that is just that. This behavior is a bit different for a static constructor. So how does a static constructor work? A static constructor is called automatically to initialize the class before: The first instance is created Or any static members are referenced. This means that regardless of what we DO, the moment we “touch” the class, the static constructor is called.

So if a static constructor fails? Once a type initializer has failed, it is never retried (for the lifetime of the AppDomain) Type will remain uninitialized Creating instances will also fail.

You should have a very good reason for throwing an exception from a static constructor.

Virtual Call In Constructor

When initializing a type in C#, constructors are invoked top-down.

First the top base constructor (object()). Then down to the derived constructors through the inheritance. So for example if we have a class Dog, inheriting from class Animal when invoking constructors the order would be: Object() - > Animal() - > Dog ().

This is important, especially when calling a virtual methods, because virtual methods are invoked bottom-up.

First the most derived overridden method and then up to all base virtual methods.

To sum it up if you call virtual methods in constructor, you may have unexpected behavior from your classes. This makes calling virtual methods in a constructor is a bad idea.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

public abstract class BaseWriter

{

protected BaseWriter()

{

// Virtual member call in constructor

this.WriteHeader();

}

protected virtual void WriteHeader()

{

}

}

public class ConcreteWriter : BaseWriter

{

private readonly StringBuilder stringBuilder;

public ConcreteWriter()

{

this.stringBuilder = new StringBuilder();

}

protected override void WriteHeader()

{

this.stringBuilder.AppendLine("--------------");

}

}

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

var writer = new ConcreteWriter();

}

}

Changing Hash Code Run-time

One of the thing we mentioned is the overriding of Equals operator for custom classes. One of the golden rules from MSDM states:

If you override the GetHashCode method, you should also override Equals, and vice versa. If your overridden Equals method returns true when two objects are tested for equality, your overridden GetHashCode method must return the same value for the two objects.

So GetHashCode is vital component for equality as it provides the hash code generation for a particular type. And the hash code is used in various hash-based collections (HashSet

If you generate a custom hash code for a type, try to use read-only properties for it. Non-read-only properties may change the hash code run-time and collections will not be notified for the change. Thus the internal structure and algorithms of the collection will not be able to retrieve and use the modified instance.

Random Numbers in .NET

The Random class is NOT a true random number generator. It’s a pseudo-random number generator. Any instance of Random has a certain amount of state, and when you call Next (or NextDouble or NextBytes) it will use that state to return you some data which appears to be random, mutating its internal state accordingly so that on the next call you will get another apparently-random number.

All of this is deterministic.

If you start off an instance of Random with the same initial state (which can be provided via a seed) and make the same sequence of method calls on it, you’ll get the same results.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

// These two instances will generate the exact same values

var firstRandomNumbersGenerator = new Random(0);

var secondRandomNumbersGenerator = new Random(0);

}

}

In .NET Framework the Random() class was initialized using the milliseconds of a TimeStamp if no other seed was provided. This meant that if we initialize two random classes after each other with default constructors, there was a high chance that they will generate the same numbers. This behavior was fixed in .NET Core, where the default constructor calls “GenerateSeed()” inner method for calculating a seed value.

RNGCryptoServiceProvider generates high-quality random numbers.

LINQ Multiple Enumeration

The easiest explanation of this issue is that we are doing extra work by enumerating the collection twice in the two foreach statements.

This is because the collection is not saved in Memory and EVERY TIME we enumarate it, we must call GetDataObjects() method.

If GetDataObjects() results in a database query, we are executing the query twice with the same result. Can be fixed by forcing the enumeration with call to .ToList() method after GetDataObjects().

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

IEnumerable<DataObject> dataObjects = GetDataObjects();

foreach (var dataObject in dataObjects)

Console.WriteLine(dataObject);

var allObjectsAsString = new StringBuilder();

foreach (var dataObject in dataObjects)

allObjectsAsString.Append(dataObject + " ");

}

}

Syntactic Sugar - Language Features in C#

Casting vs the ‘as’ Operator

When casting from one type to another fails, the CLR will throw an exception.

When using the ‘as’ operator, in case of fail, no exception will be thrown but the value will be null.

The ‘is’ operator can check the type of a variable. The operator returns a boolean.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

object str = "Five";

var num = (int?)number; // InvalidCastException

var numberAsInt = number as int?; // Here numberAsInt will be null because the cast is invalid

if (number is string)

{

Console.WriteLine("'number is string' is true");

}

}

}

Combinable Enum Values

Enum.HasFlag is the attribute typically needed when combining enums. The simple rule of thumb is that your enum should be defined like this with the Flags attribute and values spaced out by powers of 2. The reason powers of 2 are used for flagged enums is that each power of 2 represents a unique bit being set in the binary representation.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

// define our enum

[Flags]

public enum Role

{

NormalUser = 1,

Custodian = 2,

Finance = 4,

Other = 8,

SuperUser = Custodian | Finance,

All = Custodian | Finance | NormalUser

NormOther = NormalUser | Other

}

// This produces binary representation:

NormalUser = 1 = 00000001

Custodian = 2 = 00000010

Finance = 4 = 00000100

Other = 8 = 00001000

// Now because Each of the enum's bit representation

// is unique we can combine them into unique combinations:

SuperUser = 6 = 00000110 = Custodian + Finance

All = 7 = 00000111 = NormalUser + Custodian + Finance

NormOther = 9 = 00001001 = NormalUser + Other

// Notice how each 1 in the binary form lines up

// with the bit set for the flag in the section above.

But one of the more interesting things you can do is using the XOR (^=) operator because what that operator does is changes 0 to 1, and 1 to 0. So as I mentioned since there is a unique binary representation of each of the enums we can do something like:

1

2

3

// will set my user role to finance if such doesn't exist

// will set it to false if such exists

MyUserRole ^= Role.Finance

Optional Parameters

Optional parameters enable us to omit arguments for some method parameters

BankAccount(string accountHolder, decimal money = 1000) { … }

The default value has to be a constant, parameterless constructor of a value type or default(T) for some type T. When using them, we should note that the default value is embedded in the caller’s assembly and that if we change the default value without rebuilding the calling code, we’ll still see the old default value.

Using yield

If we decompile foreach, what we will see is two things:

- In the intermediate language it doesn’t exist, we only have it in C#

- It is a while loop, who works on the enumarator

So if something doesn’t implement IEnumarable, you can not foreach it.

Using yield to define an iterator removes the need for an explicit extra class when implementing the IEnumerable. This a very convenient way, with which we can remove the need to explicitly implement IEnumarable interface.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

public static class YieldNumbersGenerator

{

public static IEnumerable<int> EvenNumbers(int from, int to)

{

for (var i = from; i <= to; i++)

{

Console.WriteLine("Processing number {0}", i);

if (i % 2 == 0)

{

yield return i; // yield break allow us to stop yielding

}

}

}

}

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

foreach (var evenNumber in YieldNumbersGenerator.EvenNumbers(50, 60))

{

Console.WriteLine("Iterated number {0}", evenNumber);

}

}

Constraining Generics

When working with generic classes or methods, it can be useful to constrain the types that can be used with them.

This is called applying type argument restriction. The type argument must be or derived from the specified base class or interface.

class TemplateClass

where T : SomeClass

The type argument must be a reference type (class) or a value type (struct)

class TemplateClass

where T : class // where T : struct

The type argument must have a public parameterless constructor

class TemplateClass

where T : new()

As you’ve seen how we can apply a single constraint to generic types. While that is valuable, we can also use these constraints in combination.

class ConstrainByCombination

where T : SomeClass, new() { }