Domain-driven design essentials - Key Concepts (continued)

Chapter 2

The Domain Model - Continued

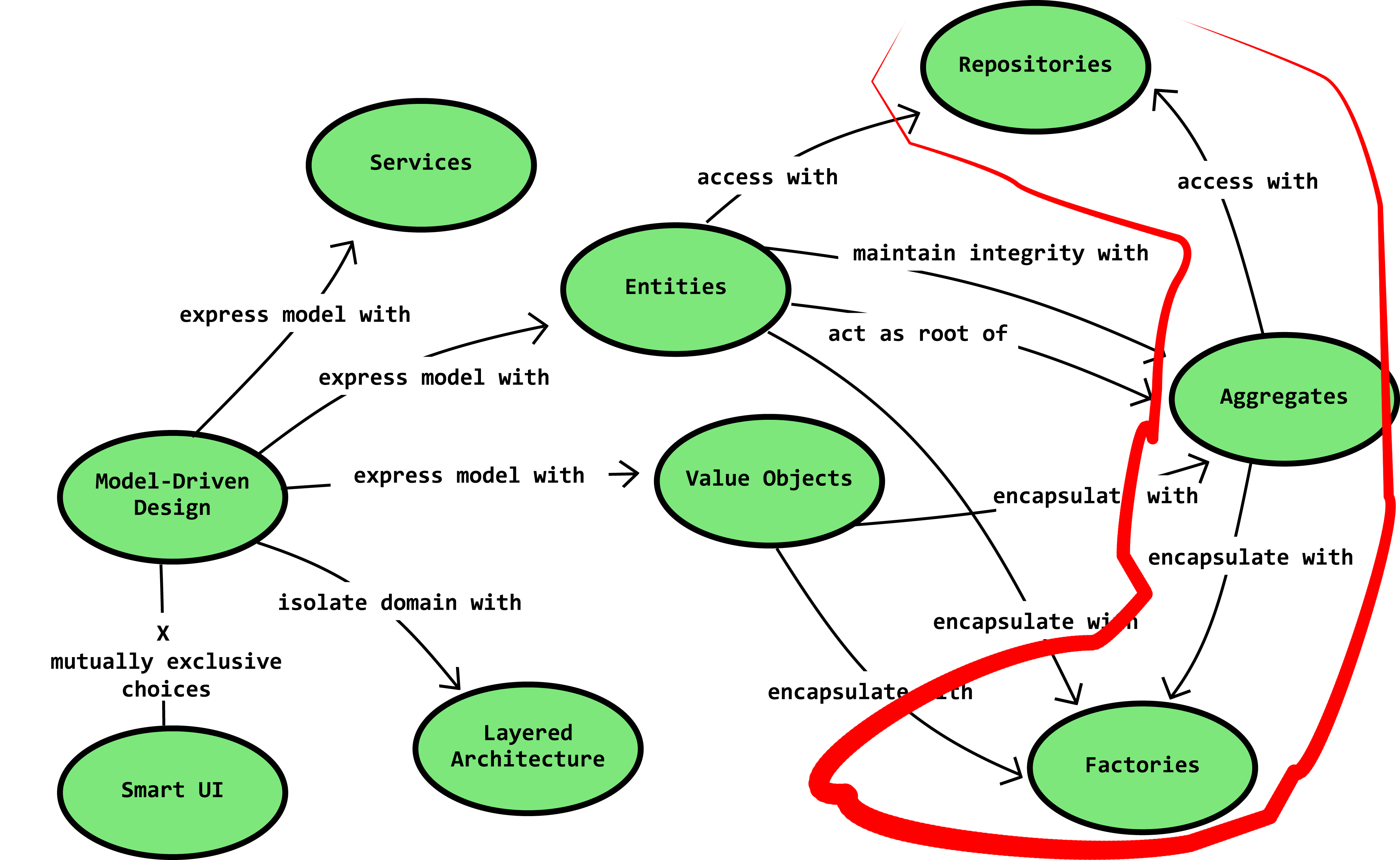

Fig. 05 DDD diagram for other Domain objects

We are continuing our journey in the Domain model.

Aggregates

As we discussed the domain model’s is composed of entities, enumerations - possibly, and value objects that represent concepts in the problem domain. Hands down the biggest problem when transferring the problem domain to a domain model in code , is the number and type of relationships between domain objects.

An example of the complexity of this issue are relationships that do not support behavior and exist only to reflect reality, another example are relationships that can be traversed in more than one direction. This defines the equal importance of not only designing the domain objects themselves but also designing their relationships.

So we are using aggregates to group related objects together, however their is also a rule that there is a single point of entry of that group of domain objects. This can define an aggregate as a cluster objects which have different types, that work together and are treated as a single unit. This cluster has a root, which is the only object with which communication is done, that is the only connection to the other “world” (layer).

Now let’s look at our Car Dealers demo, if we check the Car Dealers\Domain\Models we would see that we have Car Ads models and Dealers models, let’s further examine the first.

1

2

3

4

5

6

├───CarAds

│ CarAd.cs # Entity && Aggragate root

│ Category.cs # Entity

│ Manufacturer.cs # Entity

│ Options.cs # Value Object

│ TransmissionType.cs # Enumaration

Now from business perspective there is not need to have Manufacturers by itself without Car Ads, or no point of having Categories by itself without Car Ads. We can see that our primary business unit is Car Ads, this means that all of the other entities bellow are connected to the Car Ads. Some of you will point out that is self explanatory that when we have a Car Dealers website our primary business unit is Car Ads, and indeed it is like this, however if we look from purely structural concept isn’t it much easier to say we have Categories and we put Car Ads in them? It is, but from business perspective you can make a website for Car Ads where we have the Ads but we don’t have Categories.

But are we using this “root” only because of the business? The answer is not only. This restricts the developers when creating/using models, additionally if we scale the project, let’s say we have 500 models, instead of having 500 ways of creating a model we now only have 100. Or in other words the complexity of 500 classes communicating with each other suddenly drops significantly to 100.

So aggregate roots are cluster of objects that are saved & retrieved a single unit. The root should maintain self-integrity & validity, as it is responsible for sub entities/objects. In other words the root works as a transactional boundary, which the developer should not try to skip over. In general is a good practice to make the roots serializable.

Now let’s return to our Domain Model that we were exploring in Chapter 1 - the veterinary clinic.

We had the following design:

Appointment is the aggregate root

Client, ExamRoom, Patient, and Doctor are aggregates below it

But after discussing with the domain experts not there is this invariant in our business rules - two Appointments should not overlap one another. So we change the design.

- The aggregate root becomes a new entity called Schedule

- It contains a collection of appointments

- Every appointment logic goes through the Schedule root

- It validates the state of the application is valid

Factories & Repositories

Factories & Repositories are two concept in DDD that we can implement in multiple ways - method, classes, helper classes and so forth. The idea is that Factories & Repositories have a specific use case in DDD and it’s up to us to decide how to implement them.

Factories

Business domain objects often become too complex, and a huge thing to remember about those complex domain objects is that they cannot be in an invalid state. Due to the aim to always be in a valid state constructors for the complex domain objects tend to become quite large and difficult to use.

If we look for our simple and base system Car Deals, we can see this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

C:\Car Dealers\Domain\Models\CarAds\CarAd.cs

...

16 internal CarAd(

17 Manufacturer manufacturer,

18 string model,

19 Category category,

20 string imageUrl,

21 decimal pricePerDay,

22 Options options,

23 bool isAvailable)

24 {

...

We have seven properties for something as simple as a demo system. This is too much!

In some cases a static factory method may be good enough, a small note however is that having a method that takes seven parameters or a constructor that takes seven parameters is pretty much the same. So as our object complexity increases we can introduce the so called Builder Factories, or we can use Fluent API, which to build our objects.

So for a bigger solutions introducing a build object is recommended. To do that we mark constructors as internal, we mark all aggregate roots with an interface and we create a factory for each aggregate root.

Anti-corruption Layer (ACL)

This is a very interesting concept written in the “blue book” by Eric Evans.

“When systems based on different models are combined, the need for the new system to adapt to the semantics of the other system can lead to a corruption of the new system’s own” -Eric Evans

Even thought the main underlying concept is pretty clear. When we need to “talk” with other system, data repository or legacy code ( even “ours” legacy code ) we should protect our model from other “foreign models”. We could use this concept even on the factory level. We do this by creating an interface that only builds factories for Aggregate roots, and since all objects have internal constructors, and we can only build via the factories, we technically make ACL for what object we are able to instantiate in our system.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

C:\Car Dealers\Domain\Factories\IFactory.cs

1 namespace CarRentalSystem.Domain.Factories

2 {

3 using Common;

4

5 public interface IFactory<out TEntity>

6 where TEntity : IAggregateRoot

7 {

8 TEntity Build();

9 }

10 }

Then we use this interface to create a concrete factory implementations. We can see an example in \Domain\Factories\Dealers\DealerFactory.cs .

We talked about ACL very lightly, you can read more about it:

- Domain Driven Design Distilled by Vaughn Vernon

- Anti-Corruption Layer pattern by Microsoft (this is on a system level)

- Four strategies for dealing with legacy systems by Eric Evans

Repositories

Repositories are the main pop-up keyword that you will find when you do some research for ACL.

**NB: When we talk about *Repositories *normally people think database; DDD Repositories != EF Repositories **

Repositories are connected to the business logic inside concrete domains. For example in our system that would be Find all Car Ads by this Category. In other words Repositories work for operations on the domains, and we should only use them on the Aggregate roots.

We can split the repositories into:

- Domain only repositories – work only with domain models

- Query repositories - map domain models to DTOs

Regardless of the type our aim is to have specific repositories, and not just one generic one, with the specific business requirements - because all this speak the business language. So here comes the important distinguishment for repositories in DDD, compared to Entity Framework, we do not think in terms of persistence, but rather we take it as business logic for communication with the domain (the fact that we can have a backing store - database, behind is completely fine, but is not the main reason for existence of the component).

We implement Repositories similar to Factories using a generic interface, that limits us to only using Aggregate roots, and concrete implementations.

The Bounded Context

Is a central pattern both in DDD and Microservices, as it defines clearly borders of responsibilities in the application.

In DDD we aim to separate the different business responsibilities and from there we can also know the different responsibilities that our application would have for the business. The idea of this “modeling”, which is also known as Strategic Design, is to shift the focus to dealing with large models by dividing them into logical groups - Bounded Contexts. Where the logical groups should be very explicit about their relationships.

Using Fig. 01 Example of contexts use from Martin Fowler, we can see that each Bounded Context has

- unrelated concepts – such as support ticket in a customer support context

- and related concepts – products and customers

Different context may have completely different models of common concepts, but may share the same data identity. And here is where the biggest difference shows comparing to the classical approach, where you will have one Customer object with all the properties for the different contexts, and then by knowing you are in this “context”, you would have to figure out which properties can you use.

So to sum up, each bounded context has its own domain model, its own factories, its own repositories, its own application layer, and its own persistence layer. But what does “own” mean in a monolith app for example? Well we can just create different folders for the different context and inside of those folder create the context’s own components.

Based on all the things we said we could define some general guidelines for Bounded Contexts:

- One bounded context should not use classes meant for another bounded context. For example appointments repository should not use a billing domain model.

- In a perfect scenario bounded contexts will not be linked with a relationship. Of course this perfect scenario often does not exist, and we do have relaitonships, in those cases we try to maintain only “Ids” where those relationships exist, because if we do so we could more easily transition to microservice architecture.

- The bounded context should span across all layers of the architecture - Infrastructure, Application layer and so forth. This basically means that there should always be a clear borders for the code, and we as developers should not try to reach over them.

Databases in the Bounded Context

So how do we work with Databases in bounded context?

One approach is creating different databases for every context. This allow you to scale easily to microservices, but it may be an overengineering at the beginning, especially since our app has unknown growth and we simply do not know if we will scale. In other words this approach works for big companies, which do not have an application i.e. we are building a new app, and we know that the moment we release to production we will have like 20000 people hitting our app. Foreign keys are fictional without any relationship (like in a microservice approach).

Another approach is having one database, different interfaces for each context. This would be mean the DbContext is not one, but rather multiple for the different context, but behind the seen they are hitting the same SQL Server/MySQL instance, or even the same database inside those instances (for EF Core , it’s not an issue to work with only with the 50 tables in the context, than using all 100 that are in the database). This way you will have the architecture, and just need to migrate the data. Foreign keys are real, but you are not allowed to use domain classes from another context.

And of course we could always just have one database for the whole application. This approach is easier, but the code complexity and business logic may become so mixed up that it will be difficult to extract later. Foreign keys are real, and you are allowed to use domain classes from another context.

Which approach is the best? Tough question. The second one is the middle “golden” ground. We have one DB, so are not worry about “eventual consistency”, if a foreign key is inserted but missing we will get an error, we have that as protection, but on the other side it is architecturally split, and this makes it easier to scale up if need arise.

### Updating of Data between bounded contexts

A lot of times, probably most of the times, the business logic requires to update objects from multiple contexts. For example: A client makes an appointment, and must pay in the next 3 days. If a payment is not processed, the appointment should be deleted. As you could see this covers both the Appointment Bounded Context and the Payment Bounded Context. So how can we solve this, without going and gutting inside the different bounding contexts i.e. Apointment going inside Payment and setting some value or Payment(if not processed) going inside Appointment and deleting it? Well here comes the Domain events.

Domain Events

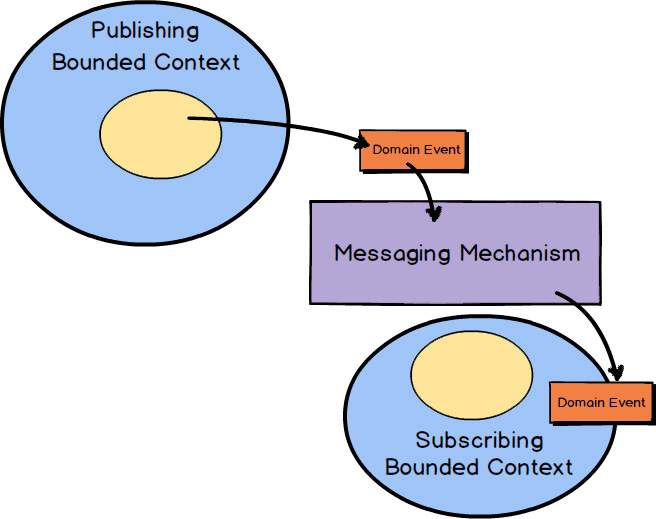

Fig. 06 Example of Domain Events

Instead of mixing business logic from both contexts, you can just fire and forget an event. Then a handler will catch the event and update the other entity. This creates decoupling and better communication between entities or contexts. If you wire the event logic with your ORM – it will be atomic and transactional. This of course is only valid for monolithic applications, for microservices we still need to implement eventual consistency patterns.

To implement Domain Events we just need tree interfaces

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

C:\Blog\src\Domain\Events\IDomainEvent.cs

1 namespace Blog.Domain.Events

2 {

3 using System;

4

5 public interface IDomainEvent

6 {

7 DateTime OccurredOn { get; }

8 }

9 }

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

C:\Blog\src\Domain\Events\IEventDispatcher.cs

1 namespace Blog.Domain.Events

2 {

3 using System.Threading.Tasks;

4

5 public interface IEventDispatcher

6 {

7 Task Dispatch(IDomainEvent domainEvent);

8 }

9 }

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

C:\Blog\src\Domain\Events\IEventHandler.cs

1 namespace Blog.Domain.Events

2 {

3 using System.Threading.Tasks;

4

5 public interface IEventHandler<in TEvent>

6 where TEvent : IDomainEvent

7 {

8 Task Handle(TEvent domainEvent);

9 }

10 }

When creating domain event some guidelines could be:

- Use past tense – AppointedScheduledEvent

- Include as little data as possible

- Do not use domain models

- Use as many primitive types as possible

- Use IDs when possible

- Include full information, only if completely necessary

- Domain events should be created by the domain layer

- But the infrastructure layer should know how to dispatch them

Borders of responsibilities

We have mentioned that Bounded context should have clear borders of responsibilities i.e. clear physical isolation, but what are the different types that we could have?

One approach could be using the Same assemblies, but we define different contexts in different folders.

Another approach could be using Separate assemblies, and we define the different contexts in the different assemblies.

And third approach could be Separate processes i.e. Microservices, with separate deployments.

We should always take the pragmatic programmer’s approach and start with the easiest one! As the more we separate – the more maintenance overhead!

Summary of the key concept in DDD

We have talked about the origin of Domain Driven Design and how it differs compared to the classical, database centric, approach.

We talked in depth about the Tactical design in DDD, which includes patterns such as Entities, Enumaration, ValueObjects, Aggragate Roots and so forth. These patterns support the creation of the low-level design decisions relating to the implementation of the system’s components and their business logic.

And since the business is the heart of our system, we talked about Bounded Context, which is technically (combined with Ubiquitous Language) the Strategic design in DDD. These patterns and practices are a framework for analyzing a company’s business domain and from that extracting the software’s problem domain—i.e., what should be solved by the software. The strategic tools are a robust framework for high-level architectural decisions, including tasks such as decomposing a system into modules and mapping the interaction between them.

Here are eight key points you have to consider when starting with Domain Driven Design

- Focus on the business logic

- Talk to domain experts

- The domain model is the application’s hearth. And every other layer communicates with it.

- Classes are encapsulated and validated

- Communication with outer layers is done through gateways like factories and repositories

- Bounded contexts define the boundaries of different business “units”

- Communication between contexts is done through events

- Break the DDD rules only for performance reasons!

Some of the things that we did not cover include Ubiquitous Language, Bounded Contexts Versus Subdomains, Context Mapping, and Event Storming.